The Battle for Narita Airport

How a decades-long struggle for land shaped modern Japan

6/9/20254 min read

SANRIZUKA, Japan — For more than half a century, this rural corner of Chiba Prefecture has been synonymous with one of Japan's most enduring civil conflicts: a bitter struggle between rice farmers and their government over land that transformed both an ancient agricultural community and the nation's approach to development.

The Sanrizuka Struggle, as it came to be known, began in 1966 when Prime Minister Eisaku Satō's cabinet announced plans to build what would become Narita International Airport on farmland that had been cultivated for over a millennium. What followed was a saga of violent clashes, political intrigue, and stubborn resistance that delayed the airport's opening by years and fundamentally altered Japan's relationship with dissent.

Roots in Sacred Soil

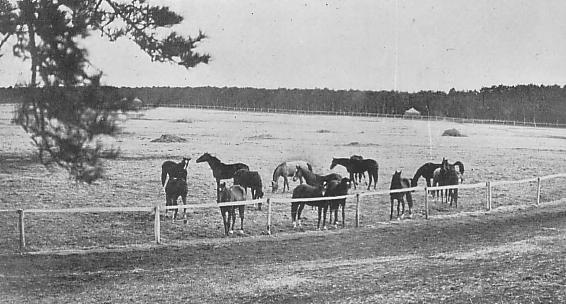

The conflict's intensity cannot be understood without grasping the deep connection between these farmers and their land. Since around 700 A.D., when an imperial edict established horse and cattle pastures here, the Shimōsa Plateau had been the backbone of agricultural life. During the Edo period, villages known as koson — "old villages" — operated beyond the reach of imperial magistrates, fostering a culture of independence and skepticism toward authority that would prove prophetic.

In the early 20th century, the area became the Imperial family's private domain, Goryō Farm, where locals grew accustomed to royal visits and developed deep emotional ties to the land. "Hearing that the Goryō Farm would disappear made everyone around here go crazy," one resident later recalled.

The region's farmers had weathered repeated upheavals. After the Meiji Restoration in the 1860s, dispossessed samurai cleared virgin land under brutal conditions. Following Japan's defeat in World War II, a new wave of settlers — dubbed "the new poor" — lived in straw huts without electricity, working dawn to dusk to scratch out livings from abandoned plots.

Each generation forged the same unbreakable bond with soil earned through sacrifice.

A Decision Made in Shadows

By the 1960s, Japan's economic miracle had created an aviation boom that overwhelmed Tokyo's Haneda Airport. After considering multiple sites, the government initially planned to build a new international airport in nearby Tomisato. But fierce local opposition forced officials to reconsider.

In a series of secret negotiations, Transport Vice Minister Tokuji Wakasa, Chiba Governor Taketo Tomonō, and Liberal Democratic Party leaders hatched an alternative: relocate the airport to state-owned Goryō Farm in Sanrizuka, where they assumed impoverished farmers could be bought off with adequate compensation.

On June 22, 1966, Prime Minister Satō announced the decision in a televised broadcast. Sanrizuka residents learned their fate not through consultation, but from their television screens.

The betrayal ignited fury that would burn for decades.

The Union Forms

Nearly every resident opposed the airport. Within weeks, the Sanrizuka-Shibayama United Opposition League was born, led by local farmers but supported by Communist and Socialist parties. Their red flag, emblazoned with white characters declaring their resistance, became a symbol of defiance that attracted leftist groups nationwide.

The government employed both carrots and sticks, offering financial incentives while deploying riot police to protect surveyors. On October 10, 1966, approximately 1,500 officers violently removed protesters who had blocked access roads with sit-ins. Airport officials celebrated installing their first surveying stakes as a "breakthrough."

But the farmers were just getting started.

Escalation and Violence

What began as peaceful resistance evolved into guerrilla warfare. Protesters threw raw sewage and stones, wielded sickles and bamboo spears, and constructed underground fortifications. Student radicals, energized by anti-war protests, joined the cause with military precision.

The violence peaked on September 16, 1971, when three police officers died in clashes at Tōhō Cross Road. Four days later, riot police forcibly evicted elderly farmer Yone Koizumi from her home, demolishing it before television cameras. The image of state power destroying an old woman's life became a rallying cry for continued resistance.

Fumio Sannomiya, a young union leader, committed suicide that October, leaving a note that read: "I detest those who brought the airport to this land. I have lost the will to keep fighting."

By 1972, opposition members had erected a 200-foot tower directly in the path of aircraft approaches, making test flights impossible. Their numbers were dwindling — from 320 founding households to just 45 — but their determination remained unshaken.

A Pyrrhic Victory

The airport finally opened on May 20, 1978, twelve years behind schedule, but only after radical groups raided the facility days before the planned inauguration, occupying the control tower and destroying equipment. Even then, only one runway operated; the second phase remained blocked by 17 holdout farming families.

Over the following decades, more than 500 guerrilla attacks targeted airport facilities. Behind-the-scenes negotiations repeatedly collapsed amid media leaks and political pressure. The struggle gradually evolved from a farmers' movement into the domain of radical fringe groups.

The last farmer was finally evicted in 2023, marking the end of a 57-year battle that had claimed multiple lives, cost billions in delays and security measures, and fundamentally changed how Japan approaches major infrastructure projects.

Legacy of Resistance

Today, Narita International Airport serves millions of passengers annually, its gleaming terminals betraying little hint of the blood spilled over its construction. But the Sanrizuka Struggle's legacy extends far beyond aviation infrastructure.

The conflict demonstrated that even in Japan's consensus-driven society, ordinary citizens could mount sustained resistance to state power. It showed how development decisions made without community input could trigger generational conflicts. Most importantly, it proved that some bonds — between people and land, between communities and their heritage — cannot be severed by government decree or corporate compensation.

In a nation that had rebuilt itself through top-down planning and collective sacrifice, Sanrizuka's farmers dared to say no. Their resistance, however costly, carved out space for dissent in a democracy still learning to balance progress with consent.

The rice fields are gone now, replaced by runways and terminals. But the spirit that drove farmers to defend their ancestral soil with bamboo spears against riot police remains embedded in Japan's political consciousness — a reminder that even the most powerful governments must reckon with the will of those they govern.